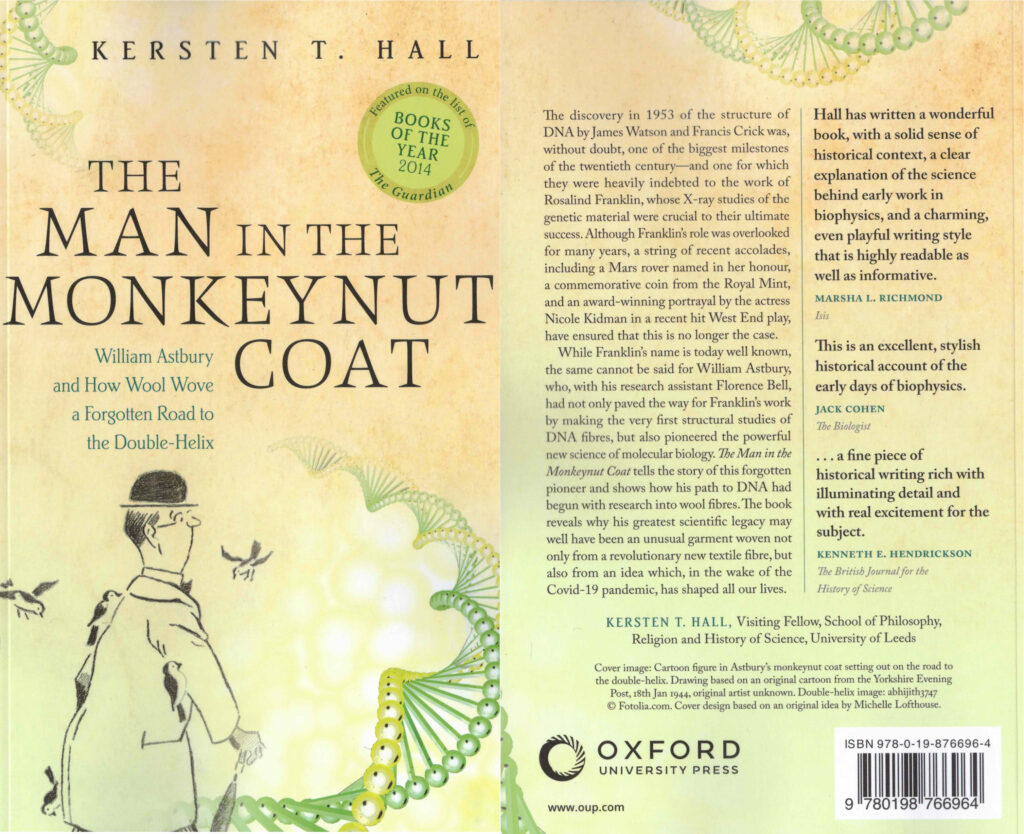

Pioneering scientist William Astbury ‘The Man in the Monkeynut Coat’ would have been delighted at recent news that #DeepMind #AlphaFold AI has broken bold new ground in biology by predicting the shape of over 200 million proteins. And I’m equally delighted that new paperback edition of ‘The Man in the Monkeynut Coat’ is pubilshed today by Oxford University Press telling the story of this forgotten pioneer who first blazed the trail in the field of solving protein structure. Understanding the molecular origami of proteins may well have all begun with Astbury’s work on humble wool fibre, & a coat woven from monkeynuts, but it’s gone on to explain how haemoglobin carries oxygen and how a vaccine can block the SARS-CoV2 virus from binding to human cells – to name but a few…